It was nearly dusk when the phone rang, slicing through the quiet rhythm of my evening. I was folding towels in the laundry room, the soft hum of the dryer masking the first few rings. The warm air smelled faintly of lavender and sun, and for a heartbeat I thought I could keep the day exactly as it was—small, ordinary, mine.

When I saw Caleb’s name light up the screen, I smiled despite everything. I still did. He had been born on a rainy Thursday, and every time his name crossed my phone it brought back the clean, stunned joy of that first cry. I tucked the phone between my shoulder and ear.

“Hey, sweetheart,” I said.

“Hey, Mom,” he answered, a little distracted. “Just checking in. Molina and I are heading out for dinner. Some bistro her cousin recommended. Paris is expensive, but she’s happy.”

I asked about the weather, whether the hotel was nice, if he’d seen the Seine yet. He gave short, polite answers. I didn’t mind. I was used to being the one who asked, the one who kept the conversation afloat like a mother nudging a toy boat across bathwater.

After a few minutes he said, “Anyway, we’ll talk more soon. Okay. Love you.”

“Love you too,” I replied, and waited for the line to go dead—but it didn’t.

There was a pause. The muffled sound of movement. Caleb must have slipped the phone into his coat pocket. Molina’s voice came next, low and close.

“Who was that, Mom?” he muttered, lowercase and careless in the way grown children sometimes are with the woman who raised them. “Something about the house again. Probably that leak in the guest bathroom.”

I held my breath, my hand still on the edge of the dryer.

Molina laughed softly. “Well, it is technically hers.”

“For now,” Caleb said, his voice going sharp in a way I hadn’t heard since he was fifteen and trying on different versions of himself in the mirror. “She’s a burden. We’ll talk her into signing the deed eventually. Guilt works every time.”

The blood drained from my face. The laundry room tilted. The dryer thumped on with indifferent rhythm and somewhere down the hall the old clock ticked like it had all the time in the world. I couldn’t move. Couldn’t hang up. I stood there surrounded by clean towels and warm light gone suddenly cold. They were planning something, and the house—my house—was only the start.

Grief, when it first arrives, moves like water. Quiet, invasive, unstoppable. I was forty-two when it drowned the life I knew. Paul died in an accident no one saw coming, leaving behind a tired wife, a teenage son, and just enough insurance to keep our lives from falling completely apart.

People brought casseroles and at the service the pastor talked about a plan that included everything, even this. I nodded because nodding is what the living do for the comfort of the living. At night, when the house settled and the refrigerator sighed and the wind threaded itself through the screens, I cried into Paul’s old flannel until the fabric smelled like salt and grief and the faintest trace of motor oil.

I remember the day I signed the final paperwork for the insurance payout. The man across the desk kept calling it a benefit—as if money could ever replace the steady patience of Paul’s hands or the way he could make Caleb laugh on a bad day by balancing a spoon on his nose. I didn’t touch a cent of it for a year. I stacked the envelopes in a fireproof box and told myself the future could wait its turn.

Then slowly, because surviving is a kind of work, I began to reshape our lives around the hollow space he left behind.

The house came first. A modest white-painted craftsman at the edge of Asheville with old bones and a good soul. I chose it because Paul would have loved the deep porch and the oak tree in the yard that split the afternoon light into coins. The first day I held the keys, I stood in the foyer and whispered, “We’re home, love,” because speaking to the dead felt less foolish than speaking to no one at all.

I made it ours with careful hands. I painted walls while the radio murmured late-night shows. I ripped up a stained carpet and found honeyed floors beneath, then rented a sander and learned, grit by grit, how to bring back a shine. I spent Saturdays at yard sales and thrift stores hunting for secondhand furniture with good bones, pieces like the house—sturdy, patient, willing to be useful again. I fixed it up myself. I could hear Paul’s voice in my head—measure twice, Lena—and I did, even when I was tired, even when the measuring felt like a prayer.

It was supposed to be the foundation for Caleb to feel safe again. I didn’t date. I worked. I worked two jobs most years, sometimes three in the summers when Caleb needed camp or books or braces. I told myself that was enough, that mothering well is its own kind of love story, a long devotion without applause.

When he got into Columbia, I cried in the parking lot of the diner where I poured coffee and learned regulars’ secrets. The scholarship wasn’t full, but we figured it out. I sold my grandmother’s ring, dipped into the insurance, picked up an overnight shift as a cashier where the fluorescent lights never dimmed. I told him not to worry about anything except studying. He promised he wouldn’t forget what I did for him. He meant it when he said it. I have to believe that, or I don’t know how to go on.

After graduation, he and Molina moved back to North Carolina for a few months. There had been a layoff. Rent was high. It was only temporary, they said. I didn’t hesitate. I gave them the upstairs and repainted the guest room myself. Molina said she liked the pale gray, and I said nothing when she replaced the curtains with something whiter, shinier, more magazine than home. When Caleb rerouted the mail to their names, when packages started arriving with labels addressed to Mr. and Mrs. Hargrave, when the bank teller greeted me as Mrs. Hargrave Jr., I smiled and told myself not to make a fuss. Hunger makes you grateful for crumbs; loneliness can look a lot like patience.

Maybe I wanted to believe we’d become a family again under one roof. Maybe I was tired of eating dinner alone at a table set for one. Maybe I didn’t listen when the house, which had learned the shape of my steps, tried to warn me.

Erosion is quiet. It wears you down grain by grain until one day you look around and realize the shoreline is gone. They started calling it our house about three months after they moved in. At first I thought it was just careless phrasing.

“We should do something about the porch,” Molina would say, running a manicured finger along the rail Paul and I had repainted on a July afternoon when the heat made the paint tacky.

“We’ve been thinking about a new stove,” Caleb chimed in, thumbs scrolling, eyes not quite meeting mine.

He added, “I’ll take care of the bills from now on. Easier if it’s all automated.”

I told myself it was kindness—help. A grown son trying to share the load. I didn’t ask why the electric bill was suddenly going to his email or why a gas company rep, chirping through a headset, called me Lena once and then Mrs. Hargrave the next. I told myself a thousand small lies the way a body tells itself it can go one more mile on an empty tank.

One Sunday, while I was at church, Molina painted the hallway. “It needed freshening up,” she said cheerfully when I came home. The soft blue I’d chosen years ago was gone, replaced with a sterile cream that matched their furniture. I stood there blinking, trying not to let it show on my face. She hugged me from behind and said, “We’re building something beautiful here.” I nodded and let her believe I agreed.

Then came the conversation about the nursery. Molina sat across from me at the kitchen table, one hand curved around a mug that left a ring on the wood, her other hand resting on her belly as if she could will a future into being by touching it enough. “We’ve been thinking,” she said, smiling the kind of smile people use when they’re about to move furniture that isn’t theirs. “If this works out, we’d love to turn your room into the nursery. You’d still have the guest room. Of course, it’s cozier.”

Caleb didn’t look up from his phone when she said it, as if the decision was already made and he was merely waiting for me to catch up.

That night, I lay awake in the very room they wanted to repurpose, listening to the wind rattle the old windows Paul had sealed years ago with his bare, patient hands. I realized how small I’d become in my own home. Every wall whispered someone else’s name now.

I reached over, turned on the lamp, and opened the drawer beside my bed. Inside was a letter Caleb had written me from college the night before a physics exam. He had thanked me for the extra money I’d sent for books and ended with, “I’ll always take care of you, Mom.”

I folded it back neatly and set it next to the deed.

Back in the laundry room the night of the call, the line between love and blindness snapped. I told myself not to listen again. I’d already heard enough. The words were burned into my memory, sharp as broken glass. And yet—because a small, wounded part of me still wanted this to be a misunderstanding—I pressed record on my phone and held it near the speaker, capturing the soft crackle and the unguarded truth.

Caleb’s voice, faint at first: “She’ll give in if we remind her how much she owes us.”

Molina’s laugh followed. “Just mention the college loans and the fact that she hasn’t paid rent since we moved in.”

I flinched. I hadn’t paid rent in my own home.

“She’s emotionally dependent,” Caleb said, as if reading a case file. “We don’t have to be cruel about it. We just need to make her feel like we’re her only real family. She is easy to guilt.”

“And once we’re on the deed,” Molina said, stirring something that clinked, silverware and glasses chiming softly, “we can finally start renovating properly.”

Another rustle. The sound of a plate being set down. The clatter of forks.

“We’ll take the master bedroom when we get back,” Molina added, almost casually. “It makes no sense for her to have the largest room when she barely does anything anymore.”

That one landed with its own gravity. I paused the recording and closed my eyes. Somewhere in Paris, at a small table under low light, they were eating food I paid for and making plans for the life I’d built.

I pressed play again.

“She doesn’t even realize how close we are to just taking over everything,” Caleb said. “And if she pushes back, we remind her about retirement homes, about healthcare. The woman’s not getting younger.”

“Possession is nine-tenths of the law,” Molina answered lightly. “We’ve been living there for years. If we had to fight it, I’m sure some judge would sympathize.”

They laughed—an old sound I had loved. I used to stand in kitchens doing three things at once, listening for that laughter the way you listen for birds in spring. But that night my stomach turned.

I saved the recording.

I did not sleep. I sat at the kitchen table with the lights off, wrapped my hands around a mug of tea that went cold without my noticing, and listened to the house breathe. The dining room remembered birthday candles blown out by sticky fingers. The backyard held Paul’s handprints in the concrete we poured for the patio, one slightly smudged because Caleb had bumped his father’s elbow at the worst possible second. The hallway remembered the soft thud of a soccer ball against the baseboard and the sharp, guilty “Sorry, Mom!” that always followed.

I had given everything.

By morning something inside me had settled. Not peace, not yet, but a quiet certainty. I would not plead for space in my own home. I would not let them decide what I was worth.

I opened the drawer, took out the deed, and drove to Joanna’s office without calling ahead. Joanna had known Caleb since he was in diapers. She danced at my wedding and stood beside me at Paul’s funeral in a dress borrowed from her sister because the black one she owned was too tight across the chest—these are the useless details you remember about the people who stay.

She waved me in, shut the door, and poured coffee into the chipped mug she kept for me on the corner of her desk.

“You look like someone who’s come to set something straight,” she said.

I slid the deed across the wood. “Can you confirm I still hold sole ownership?”

She scanned it, eyes quick and careful. “There’s no co-signers, no liens, no additions. The house is entirely in your name, Lena.”

I told her what I’d overheard. Not every word—just enough. Joanna’s face changed the way mountains change when a cloud passes: not much at first, and then all at once. Her eyes hardened. She reached for a legal pad.

Over the next hour we mapped it out: legal protections, timelines, contingencies. Her pen moved in straight, uncompromising lines. “If they try anything before closing, call me. If you feel unsafe, call me first and then the police. You’ll do a private listing. No sign out front. I’ve got a realtor who won’t ask questions he doesn’t need answers to. You’ll pack only what is yours. We’ll document the rest.”

I didn’t cry. I didn’t raise my voice. I signed what needed signing, made copies, set reminders on my phone like a woman preparing for a storm she would not be trapped inside again.

By afternoon I was sitting in a quiet office two towns over with Marcus, a realtor Joanna trusted. He was a no-nonsense man with kind eyes who knew how to listen faster than he talked. When I told him I needed a quiet sale and a fast turnaround, he didn’t flinch.

“We’ll price it to move,” he said. “I have buyers who love that street and don’t need an open house.”

He walked through the rooms with a polite distance that felt like respect and took photos the way a doctor takes a pulse—efficient, attentive, without sentimentality. He didn’t comment on the dents in the baseboard or the patch of paint where a child once taped a poster of a rocket ship. He didn’t say, “It’s a shame.” He said, “We can do this,” and I liked him for it.

I started packing that night. I took only what I had brought into the house. Photos in frames where the glass had been wiped so many times it shone like water. Linens I had washed until the edges softened. The worn leather chair Paul had loved, its arms darkened by the oil of his elbows, the curve of his weight still faintly there. Books I had collected over three decades—novels that had kept me company at two a.m., cookbooks with notes in the margins, a battered poetry collection with a grease stain on page twelve because grief doesn’t ask you to wash your hands before it arrives.

Everything else I cataloged. What was Caleb’s went into boxes I labeled clearly: CALEB—UPSTAIRS CLOSET; MOLINA—BATH; C+M—OFFICE. I hired two men from the bulletin board at church who loaded the boxes into a moving truck with careful hands. I prepaid for a storage unit, tucked the contract into a folder, and left the code with Joanna in case they came looking. I didn’t tell anyone I was leaving.

On a gray Tuesday I signed a contract at Marcus’s office and walked out into a rain that felt like a benediction. That night, alone in the kitchen, I wrote a note and set it on the counter where Caleb and Molina would see it when they walked in.

Surprise! A burden did this.

I set down the keys beside it, locked the door from the inside, and exited through the garage one final time. In the car, I sat for a minute with my palms flat on the steering wheel. The town blurred behind me like a painting washed in rain. Ahead, the road began to open.

They came back on a Wednesday. I knew not because they told me, but because the calls began just after noon and didn’t stop for hours. First Caleb, then Molina, then Caleb again. Missed call, voicemail, text, another call. Each one more frantic than the last.

“Mom,” his voice crackled through the first voicemail. “The keys aren’t working. Did you change the locks? What’s going on?”

The second was shorter, harsher. “Lena, this isn’t funny. Where is everything? Where are you?”

By late afternoon the messages shifted tone, a trick sugar knows well. Molina’s voice filled one: syrupy, sweet, but sharp underneath. “We’re just really worried, okay? Please call us. Just let us know you’re safe.”

Safe. I held the phone and said the word aloud to my empty kitchen in the new apartment in Charlottesville, tasting it like something rare and expensive. For the first time in years, I was.

Later that night, Caleb left a final message, his voice strained. “We found the note. I don’t know what you think you heard, but you’ve made a huge mistake. This is our home, too, and you had no right—none—to sell it. We’re talking to a lawyer. You’ve really done it this time.”

I saved that one, too. I didn’t respond. I stirred sugar into a cup of coffee I didn’t really want and watched dusk pull itself over the new neighborhood like a blanket. Let them yell into the void. Let them wonder where the line between control and love finally snapped. I had no interest in pulling them across it.

The house was gone. The door no longer opened for them, and my silence, at last, spoke louder than anything I had ever said.

They demanded a meeting. Caleb’s message came in short and sharp: “Tomorrow. 10:00 a.m. Café on Main. If you don’t show, we’re coming to your office.”

So I showed. I arrived at 10:05, not out of rudeness but intention. Caleb and Molina were already seated, postured in practiced indignation, hands around untouched mugs. The café smelled like citrus and espresso and wet coats.

I didn’t greet them. I sat. I set my phone on the table, screen up, and pressed play.

Our voices and theirs spilled into the small noise between us. “She’s a burden.” “We’ll take the master bedroom.” “Guilt works every time.” The words, returned to their owners, lost their costume and stood there naked and mean. Molina paled. Caleb’s jaw went tight, then tighter.

“You misunderstood,” he said finally, flat as a shut door.

“No,” I answered. “I finally understood.”

“You blindsided us,” Molina said, leaning forward, voice soft and cutting. “You sold our home out from under us.”

“It was never yours,” I said. “It was mine—paid for, maintained, protected.”

Caleb scoffed. “After everything we’ve done for you—”

“Yes,” I said, meeting his eyes and not looking away. “And you taught me exactly what not to become.”

Silence can be a bridge or a cliff. They didn’t know how to cross the one I offered. I didn’t give them time to find a way.

“There will be no money,” I said. “No access to my accounts. No forwarding address. No second chances.”

Molina opened her mouth, closed it. Caleb’s fists whitened on the table.

“I’m your son,” he said at last, as if the title alone should unlock something.

“And I was your mother,” I said quietly. “Not your asset.”

We sat with that. The café door opened and closed; someone laughed; the espresso machine hissed. Life went on around us, uninterested in our small storm. I slid an envelope across the table. Inside were the storage unit details and a neatly typed inventory of their things.

“You’ll need an ID,” I said. “I left the code with Joanna as well.”

I stood. They didn’t call my name.

The quiet in my new apartment felt different. It wasn’t the aching kind I used to fill with other people’s needs. It was soft, whole. I wasn’t waiting for someone to knock or call or ask for something they had already decided I owed them. I learned the way light moved across the floor from east to west, and how the building’s old radiator clicked three times before giving in to heat.

In the mornings I made real tea, not the half-cold cups I forgot on counters while solving someone else’s emergency. I sat by the window and watched sparrows argue on the ledge and read entire chapters without interruption. Some days I didn’t speak to anyone, and I liked it that way.

But I did not disappear.

A flyer at the library led me to a community center three bus stops away that hosted weekly grief and boundary-setting groups. The first night felt strange. I sat in a circle of folding chairs under humming lights and said my name like a person starting over.

We went around, each of us holding our stories like fragile things we weren’t sure would survive air. There was an ICU nurse who had forgotten how to say no, a man whose brother would not stop borrowing money, a woman my age who had turned her spare bedroom into a storage closet for other people’s chaos. We didn’t fix each other. We listened. Sometimes that’s the only mercy available.

After a few weeks a woman named Sabria pulled me aside. She ran a shelter for single mothers near the edge of town—ten beds, a playroom, a kitchen that made miracles out of donated beans and rice. “We could use someone like you,” she said. “Not to preach. Just to sit with them. Tell the truth.”

So I started showing up on Tuesdays. At first I folded tiny shirts and sorted diapers by size. Then I began to stay for the evening meal and the hour after, the hour when exhaustion loosens tongues. I sat on worn couches with young women who had no one left to believe in them. I learned the metrics by which social workers measure progress—days without crisis, appointments kept—and I learned another metric that mattered more: how long a woman could tell her story without apologizing for it.

I told them some of mine. Not the bitter parts, not the recording or the café, just enough to say: You are not alone, and there are doors that you can close even if your hands shake when you do it.

A Tuesday in late September I walked home in the thin blue of evening and realized I hadn’t thought about Caleb in days. Not with pain. Not with anger. Just distance, clean as a line drawn with a ruler. Not every loss is a wound. Some are the first step toward something that finally belongs to you.

A year passed in the quietest way. No dramatic changes, no declarations—just steady days—honest, unspectacular, mine. I bought a basil plant for the kitchen sill and didn’t kill it. I learned my neighbor’s dog’s name. I replaced a lamp and assembled it without crying. On a Saturday I took the bus to the botanical garden and sat on a bench while children ran past, loud and alive, and I didn’t think about whether any of them would call their mothers when they were grown.

The anniversary snuck up on me. I only realized when the first yellow leaf fell outside my window. Autumn had been Paul’s favorite season. When Caleb was little, he would fling himself into piles of leaves with a shriek so pure it made passing strangers laugh.

I made tea and sat at the kitchen table with my journal. No one expected anything of me that day. No calls. No demands. I opened to a blank page and wrote a letter—not to Caleb, not to anyone else—just to me.

You were never a burden. You were the foundation. You kept it from falling apart when the wind blew and the water rose. You carried what no one saw and gave more than anyone gave back. And when they tried to reduce you to your usefulness, you chose to walk away. That wasn’t cruelty. It was clarity.

I signed it without flourish or apology and slid the paper under the salt shaker like a promise.

Later I walked. I didn’t mean to go near the old neighborhood, but my feet knew the way. I passed the bakery that used to sell the kind of birthday cakes I couldn’t afford and the hardware store where Paul once explained bolts to a clerk old enough to be his father. I turned onto my old street and slowed—not to look back, but to pass through.

The house stood there, familiar and distant. Someone had painted the door a blue brighter than I’d ever choose. A new porch swing hung where the old one had creaked. The oak still split the light into coins.

It didn’t hurt like I thought it would. I didn’t linger. I didn’t hope anyone would look out a window and see me and wave me over as if I had been missed. I kept walking. At the end of the block a child on a tricycle shot across the sidewalk and his mother called after him with a voice full of both terror and love. I nodded to her like we were part of a club that had no meetings and no dues and still cost more than we thought we could pay.

I didn’t lose my son. That truth settled slowly without bitterness. I lost the version of him I wanted to believe in—the boy who would never turn away, the man who would remember the hands that built his world. What I let go of wasn’t a child. It was the illusion that he saw me.

And what I found in the space left behind was a life with room for my own name.

In the second year I painted the small bedroom a soft blue that reminded me of the first hallway before the cream and the pretending. I bought a chair for it—a simple wooden thing that fit my back—and read in it at night with the window cracked, the city noise drifting in like proof that I was part of something without having to carry it.

Once, around Christmas, a number I didn’t recognize flashed on my phone. I let it go to voicemail. Later, washing dishes, I pressed play. Caleb’s voice, older by a kind of weight I couldn’t measure, filled the little kitchen.

“Mom. I—” He stopped. Cleared his throat. “I heard from Joanna. We got our things. Thank you for that. We… we moved. It’s smaller, but it’s ours. Molina’s expecting in March.” Another pause, and then a breath that sounded like he had surprised himself by taking it. “I wanted to say I’m sorry. For the things I said. For the things I let happen. I don’t know how to fix it. I just… I wanted you to know I’m trying to be better than I was.”

The message ended there. No number to call back. No request for money. No strings. I stood at the sink with my hands in soapy water and felt something shift—not forgiveness exactly, not yet, but a loosening around the place where the rope had burned.

I dried my hands and made tea and, because I have learned what to do with things that arrive before I’m ready for them, I wrote the date on an index card and tucked it into my journal.

People talk about fresh starts like they arrive on New Year’s Day with fireworks. Mine came like morning—incremental, quiet, inevitable if you live long enough. I planted herbs on the sill and learned when to pinch the basil so it wouldn’t bolt. I kept showing up on Tuesdays. I bought a coat at a thrift store that made me look like someone who belonged to herself.

On a spring afternoon I watched a girl at the shelter draw a house with a purple crayon—square, door in the middle, two windows, a lopsided heart on the roof. “That’s where I’m going,” she said, tapping the crayon to the heart like she could nail it in place. Her mother smiled, tired and luminous. I sat with them and thought of porches and keys and the clean, ordinary sanctity of a room you can call yours.

What I know now is simple and hard-earned: the people who love you will show you who they are when they think no one is listening. Believe them the first time. And if you can’t, believe the second. And if you still can’t, call a friend who brings a chipped mug to your side of the desk and draws a map out of the life that is drowning you.

I walk home most evenings. Sometimes the sky is theatrically beautiful and sometimes it’s just sky. I pass the same row of small shops and the same man who plays the same three songs on a saxophone and I put the same folded dollar into his case because we are all repeating ourselves, trying to make music of what we have.

When I reach my building, I climb the stairs and fit my key into the lock of a door I chose—a door that opens because I say so. Inside, the tea kettle waits. The basil leans toward the light. The radiator clicks once, twice, three times, and then the heat begins.

This, too, is a kind of happily ever after: not a trumpet, not a parade, but a woman setting down her bag, washing her hands, and sitting in the quiet she learned to claim. A life with no sign out front and no one on the deed but me.

News

BREAKING: My Son Gave Me a Choice: Either Serve His Wife or Leave. I Smiled, Grabbed My Bag…

My shopping list was still in my pocket when I walked through the apartment door, arms full of groceries from…

I Thought I Knew My Children Until The Plumber Discovered What They Were Hiding In The Basement and Said: ‘Pack your things and leave the house immediately!’

My name is Anita Vaughn. I am sixty‑three years old, a widow, and for more than four decades this house…

I Counted 21 Times My Children Interrupted Me While I Read My Husband’s Will. They Smirked, Whispered, And Looked At Each Other Like I Didn’t Exist. Days Later, I Pressed Record As The Lawyer Entered.

The first thing they did was toss my husband’s muddy work boots into the trash—the ones he’d left by the…

I Won The Biggest Lottery Jackpot In State History — $384 Million — But I Didn’t Tell Anyone. I Called My Mom, My Brother, And My Younger Sister, Saying That I Was Short On Money And Needed Help.

My name is Mark. I’m thirty-two, the oldest of three, and the family’s invisible cushion—always catching, never caught. I’m a…

BREAKING: When I Learned My Parents Gave The Family Business To My Sister, I Stopped Working 80-Hour Weeks For

The pen hovered over the document, my father’s signet ring glinting under the office lights. I watched, frozen, as he…

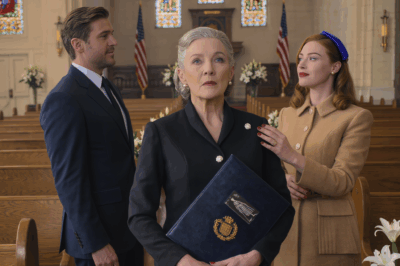

JUST IN: At my husband’s funeral, my daughter-in-law mocked my dress. She had no idea who I was.

The chapel was silent except for the low hum of the organ and the soft scrape of shoes against marble….

End of content

No more pages to load