I was the only one who cared for my dying father for years. When he passed, he left my sister a $950,000 house. I got the old, crumbling lake house. “Guess you were the worst daughter,” my sister laughed. But when I stepped inside that house, what I found changed everything.

“To my daughter, Patricia, I leave my primary residence at 4521 Maple Drive, valued at approximately $950,000.”

Patricia’s perfectly manicured fingers tightened around her Hermès purse. The somber mask she wore had hairline cracks of triumph underneath.

“And to my daughter Margaret, I leave the lakehouse property on Clearwater Road.”

The lawyer’s voice stayed perfectly even. He didn’t say that the lakehouse was a rotting cabin I hadn’t seen in fifteen years, that raccoons loved it, that the porch pitched like a drunk.

Patricia waited thirty seconds after we left to twist the knife. “Well, Maggie,” she said, using the nickname that fit me the way a stone fits your shoe, “I guess we know who Dad really loved.” Her laugh rang like broken glass. “Guess you were the worst daughter, after all.”

I could have listed the three years of driving two hours each way to change bandages and coax food past a throat that forgot how to swallow. The physical therapy appointments, the nights I slept in an armchair while breathing with him through the terror. I could have counted on both hands the number of times she visited and still had fingers left. But I had learned: wrestling Patricia only makes you muddy. The pig enjoys it.

Clearwater Road meandered like a memory through woods that used to be younger. Pines crowded the ditch line. A pair of wild turkeys trotted across as if they owned the deed. I parked by the leaning mailbox, the lake winking through bare branches, and stared at my inheritance.

Two acres of knuckled weeds and sighing shingles. A porch that had settled into a permanent apology. Paint peeled off the shutters in papery scrolls. The front step creaked in a single syllable: why.

“Perfect,” I muttered. “A money pit with a view.”

The key was old enough to have opinions. It turned with a stubborn groan. I pushed the door—and stopped.

It smelled like lemon oil and vanilla instead of dust and mouse droppings. Afternoon light stroked floors that shone as if a patient hand had learned the grain by heart. White sheets draped furniture shaped by comfort rather than hunting trophies. In the kitchen, the coffeepot exhaled a thin curl of steam. Warmth from the hot plate licked my palm.

Either someone was squatting in my newly inherited shack, or my father’s secrets had keys.

“Hello?” My voice sounded larger than me. “Anyone here?”

Not silence—held breath. A pause that felt like a person standing just out of sight, deciding.

The living room had a flatscreen on a low cabinet and a bookshelf fat with paperbacks: mysteries, romances, dog‑eared at the good parts. A blue throw folded into perfect thirds. Coasters without water rings. A life.

In the bedroom, a photograph waited on the nightstand. Dad—older hair, younger smile—stood with a silver‑haired woman in a yellow sundress. Her blue eyes were the kind that crinkled when they forgave you for being human. He held her like a man allowed to set his shoulders down.

“Well, Dad,” I told the glass. “Look at you.”

Footsteps moved across the kitchen. Not sneaking; familiar. I slid the photo into my purse as if I had any right to it and followed the sound.

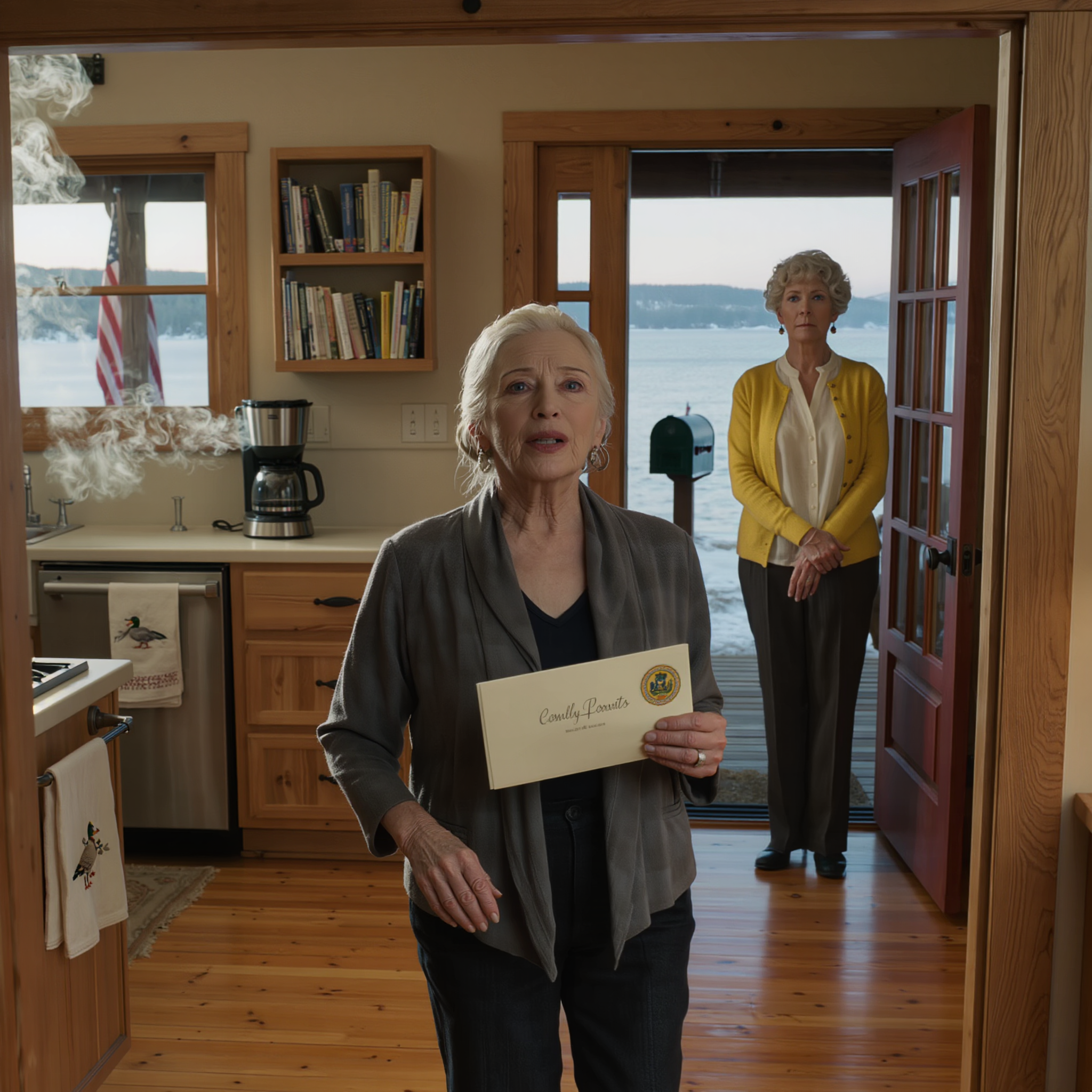

She was at the sink, washing cups, humming half a melody that might have been from the radio twenty years ago. In person, she was more striking than the picture—one of those women who carry themselves like a promise they made to themselves and kept.

She turned when I cleared my throat. The blue of her eyes went sharp, then warm. She didn’t look surprised; she looked ready.

“You must be Margaret,” she said, drying her hands on a towel embroidered with tiny ducks. “I’m Eleanor. Eleanor Walsh.”

“Eleanor,” I said, tasting the shape of it. “And you…?”

“Someone your father cared for very much.” She rehung the towel precisely. “I’ve been expecting you.”

“Expecting me? That’s interesting. I only learned you existed five minutes ago.” I sat without asking. “How long did you and my father… care?”

She poured coffee for herself and, deliberately, not for me. “Seven years. Companions. Friends. More than friends.”

Seven years. The arithmetic ran its fingers down my spine. The first of those years my mother was still in her body, dwindling. I knew how to grind anxiety into soup and calendars and gentle hands. I did not know how to place this woman in the math.

“Mistress,” I said, because I needed a word that could be angry.

Eleanor’s gaze didn’t flinch. “I was the woman who made him laugh when your mother was dying, when your sister was too busy to show up, and when you were carrying more than one person should. I did not take your place. There was a gap no one could fill.”

“Don’t make this about me.” The chair barked against the floor as I stood.

“I’m making it about the truth.” Her calm made me want to run. “A faithful man can be faithful to grief. He found comfort. He did not run.”

Rage wants simple villains. Life never has them on sale.

“Where does that leave me?” I asked. “Legally, this is my house.”

“Actually,” she said, the word neat as a scalpel, “it isn’t.”

She pulled a manila folder from a drawer, set it on the table, and opened it like a dealer laying down a hand you can’t beat. Signatures. Notary stamps. A trust instrument bound with a blue ribbon.

“Three years ago your father transferred the structure and its contents into a living trust. I’m the beneficiary. The will leaves you the parcel—the dirt. The house belongs to the Clearwater Trust.”

“You’re telling me I inherited ground but not walls.”

“Essentially.”

Somewhere in my head Patricia laughed again, ugly and small. Worst daughter.

“There’s more,” Eleanor said, the way people say there’s a second wave.

She slid two envelopes across the table. Dad’s careful hand spelled our names. My throat closed around mine.

“My dearest Maggie,” the letter began, and I sat down because my legs had opinions too. “If you’re reading this, then you’ve met Eleanor and discovered my secret. You’re angry and you should be. Let me explain.”

He had written like a man praying his words could be heavier than his mistakes.

“The house on Maple Drive isn’t mine to give. It belongs to your sister. Three years ago, with your mother’s medical bills, I was headed for foreclosure. Patricia offered to buy the house ‘quietly’ so I could remain as a tenant until I died. She paid $950,000. The will only recognizes what already is.”

I looked up. “So Patricia has owned Maple Drive for three years.”

“Correct,” Eleanor said.

“And let everyone think he was bequeathing it now.”

“Also correct.”

The next paragraph made heat prickle my scalp.

“What your sister doesn’t know: it wasn’t entirely legal. As my financial power of attorney, she sold the house to herself below market value. That is elder financial abuse.”

In my mind I saw Patricia at Dad’s dining table with her branded pen and her branded smile, sliding page after page across for him to sign while she told me she’d ‘handle the boring stuff’ so I could attend to ‘the caregiving.’

“I documented everything,” Dad had written. “Bank records. Emails. The notary who came on a Sunday. I kept quiet because I needed her help and hoped she would do right. I was a coward. I’m trying not to be now.”

He had always apologized better on paper.

“The Clearwater parcel is worth more than anyone thinks. I hired a survey last year—water rights, development interest—land alone at $1.2 million. More importantly, there is something here Patricia doesn’t know about.”

“In 1987, while repairing the foundation, I found artifacts. I told no one—not even your mother. I photographed, mapped, and hid the record. Work with Dr. Sarah Bennett at the State Archaeological Commission. She will survey after I’m gone. This belongs to history. The finder’s fee and property rights should secure your future.”

Coordinates followed. A single sentence like a hand held out: “Please forgive me if you can, and even if you can’t, do the right thing with what I’m giving you.”

The closet still smelled like him—cedar, starch, something sweet he’d favored after the stroke. The loose floorboard lifted with a gray sigh. The metal box under it had been mummified in tape that yellowed into amber.

Inside, time breathed. Photographs of the cabin’s bones and, beside them, shards of pottery, copper bells, chipped tools, etched stone, beads the color of river glass. In the journal his handwriting shrank to fit the precision: weather, trench depths, coordinates, sketches, a care I had not seen him give anything except my mother.

“My God,” I said.

Eleanor stood with her hands folded, as if we were in a chapel. “He protected it for thirty‑seven years.”

On the last page a business card was clipped. Dr. Sarah Bennett. On the back, a date and time in his steady hand: Tomorrow. 2:00 p.m.

“He arranged it,” Eleanor said softly. “He wanted this to be easy for you in the ways he could make it easy.”

My phone vibrated. Patricia: Hope you like your shack. Maybe make it a trailer park. LOL.

I held the screen out. Eleanor winced. “She will learn,” she said, and poured me the coffee she hadn’t offered earlier.

Dr. Bennett arrived at exactly two, Jeep dusted in honest dirt, cases stacked like promise. She wore field pants, a faded button‑down, and the kind of boots that never apologize.

“Mrs. Patterson? Sarah Bennett.” Firm handshake. Quick eyes. “Your father’s documentation is exceptional.”

She walked the property with a notebook and a GPR unit that looked like a baby stroller. She flagged a grid in orange tape, then rolled the machine back and forth with the quiet concentration of someone reading under her breath.

“Remarkable,” she said after an hour. “Subsurface anomalies consistent with postholes, hearths. The site extends beyond the immediate structure. We could be looking at a substantial pre‑Columbian settlement—perhaps eight centuries.”

“What does that mean for… logistics?” I asked, pretending I wasn’t calculating.

“For history: significance. For you: an archaeological easement, compensation for access, finder’s fee, potential percentages should institutions acquire anything. Also—media interest.” She smiled, apologetic and unapologetic at once. “People love a story.”

When she left, my phone rang before I could make tea.

“How’s the cabin?” Patricia’s voice had a syrup that stuck to the teeth.

“Full of surprises,” I said. “Question: when listing waterfront parcels, do water rights disclosures go before or after the appraisal?”

Silence, then: “Selling already?”

“Maybe. The land value is… robust.”

“How robust?”

“More than Maple Drive,” I said, and hung up because I had earned that pleasure.

She arrived the next morning in her white BMW at a diagonal like an accusation. Eleanor opened the door before I could.

“We need to talk,” Patricia said, shouldering past.

“Coffee?” I asked, holding up Dad’s mug that read World’s Greatest Father. The words no longer stung; they fit.

“What game are you playing?” she demanded.

“No game. Exploring options. Property owners do that.”

“There’s no way that dump—”

“Dump?” Eleanor’s voice developed an edge. “This home has been maintained with care for seven years.”

Patricia’s gaze flicked. “And you are?”

“Eleanor Walsh. Your father’s companion.”

“His what—girlfriend?” I offered. “They were devoted.”

She went through three colors in ten seconds. “He would never—”

“Be happy? Keep secrets? Choose himself, once?” I asked. “He did, Patricia.”

She pulled out her phone. “I’m getting a real appraisal.”

“Do,” I said. “Maybe wait until after the archaeological survey.”

She froze. “Archaeological what.” Not a question; an alarm.

I slid the journal across the table. She turned pages until the photos told a truth her mouth refused to say. “This can’t be real.”

“Dr. Bennett thinks otherwise. Her team arrives Monday.”

Patricia closed the journal with fingers that tapped a nervous beat. “I want half.”

“Half of what?”

“Whatever this is worth. I’m his daughter too.”

“You already got your half,” I said, pleasant as sugar. “$950,000.”

“That’s different.”

“Is it?” I leaned forward. “We can discuss Maple Drive. The power of attorney. The below‑market sale. The Sunday notary. Or we can keep it tidy.”

She forgot to breathe for a second. “You can’t prove—”

“Dad documented everything,” I said. “Bank records. Emails. Witnesses. The DA calls it elder financial abuse.” I let the phrase sit between us until it grew teeth. “Or we can call it a civil matter resolved between sisters.”

“What do you want?” Her voice was smaller than I remembered.

“Wire me $475,000—half the value of Maple Drive. It’s back pay for three years of care.”

“That’s extortion.”

“It’s arithmetic.”

“I want it in writing.”

“Already drafted,” Eleanor said, and produced an agreement from the folder that had been waiting like a quiet friend. “Thirty years as a paralegal. We tend to anticipate.”

Patricia read. Each page tightened her jaw. She signed as if the pen were a knife and the paper could bleed.

“You’ve changed, Maggie.”

“Yes,” I said. “I finally priced my time.”

The wire hit the next afternoon. My bank app showed numbers I had never seen next to my name. I took a walk down to the dock and cried anyway—not for the money, but for the ledger that had finally balanced in a place no bank could see.

Monday brought trucks. Tents. A hum of voices and the soft, relentless brush of dirt off history. Dr. Bennett’s team moved with a choreography I could have watched like a ballet. Strings defined squares. Bags labeled by grid. A sifter singing its sand‑through‑mesh song.

They found a hearth first. Then a posthole ringed with darker soil like a bruise. Pottery whose pattern echoed the lake surface on wind. A stone carved with lines that made even the chatterers hushed.

“This is extraordinary,” Sarah said, and this time she didn’t temper it. “We are going to rewrite a paragraph of the state’s pre‑contact history. And Mrs. Patterson—you will be compensated accordingly. The easement alone could be seven figures.”

That evening Eleanor opened a bottle of wine on the porch. Floodlights bathed the dig in moon‑colored clarity. The lake held the sky like a secret.

“He would be proud,” she said.

“He is,” I said, surprising myself with how sure I felt.

Patricia texted: Saw news trucks. We should renegotiate.

I typed: Our agreement is signed. See you on the evening news.

Two weeks later National Geographic arrived with polite chaos. The producer, Jennifer Martinez, was small and efficient and wore sneakers that did not pretend to be anything else. She made me a mic and a promise to be kind.

“How does it feel,” she asked, “to go from the daughter people pitied to a woman who may have just become the wealthiest person in the county?”

“It feels like justice,” I said, and the word did not feel like revenge. It felt like air.

Patricia tried to step into frame with a blazer and a story. “I’m Margaret’s sister. Our father always knew this land was special.”

Jennifer’s eyebrows smiled. “But you didn’t inherit it.”

“Well, no, but family is—”

“We’re preserving,” I cut in. “Everyone wins when history is done right.”

After the cameras, after the crew, after the day’s dig had been tucked under tarps like children, Eleanor and I walked to the dock. A heron stood editorial at the reeds. The evening smelled like pine and something clean you can’t bottle.

“What now?” she asked.

“Now we sign the easement. We bring in descendant communities to lead interpretation. We make sure the museum doesn’t take without giving back. We build a scholarship. We do it right.”

“You learned to speak their language fast.”

“I learned to listen.”

In the weeks that followed, I met with a lawyer who translated the trust and easement into plain English without making me feel small. We structured payouts so the taxes didn’t take a bite the size of a wolf. We wrote the museum agreement with clauses that made sure artifacts stayed within two counties of their home unless the Nations agreed otherwise. The Tribal Historic Preservation Officer came to walk the site with Sarah. We paused work on a square when he asked us to. Listening is a tool.

Patricia called once more, late at night when old habits come dressed as emergencies. “We should rethink the split,” she said. “The TV money—”

“There is no TV money,” I said. “There’s documentation and a modest production fee that funds the field school. You already received your share.”

“Maggie—”

“Good night, Patricia.”

After that she stopped calling. I heard later that Maple Drive hit the market. The carrying costs of a trophy home do not care for the feelings of the person who bought it wrong.

Six months later Archaeology Today ran a cover: THE ACCIDENTAL ARCHAEOLOGIST. Inside, a photo of me in a sun hat I would have mocked a year earlier. Sarah insisted I looked like an authority. I looked like a woman who had finally stopped apologizing for taking up space.

The foundation paperwork arrived with a stamp and a weight I recognized: responsibility disguised as an envelope. We called it Clearwater Futures and wrote a mission that funded field schools, community partnerships, and small grants for descendant youth who wanted to study anthropology, history, law—whatever they chose. The first scholarship went to a young woman who showed up every weekend to volunteer at the sifter and knew more about care than any credential.

On quiet mornings I still visit the dock with coffee. I talk to my mother like she sits on the step above me and lets the sun have her hair. I tell her about the day we found a bead the size of a raindrop and the way the whole crew cheered like a team that understood what winning means. I tell her about Eleanor teaching me to make soup that tastes like a house smells when it forgives you. I tell her about the letter I wrote back to Dad in my head and how it ends the same way every time: I forgive you because you made it possible for me to forgive myself.

Sometimes Patricia appears at the edge of my thoughts like a figure behind a screen door. I hope she learns to be someone whose first move isn’t to take. I hope the house sells to a family who laughs in the kitchen and gets splinters on the back deck and pays the taxes without worrying. I hope small decencies happen to her until she begins to practice them too. Hope is cheaper than the other thing and spends better.

As for me, I keep the lakehouse. It is still Eleanor’s legally—the trust weaves the building to her name—but our lives are braided now. Paper doesn’t always reflect reality. We redrafted the occupancy clause to read like the truth: we share the porch, the coffee, the mornings when the fog lifts and the excavation lights click off one by one like stars remembering how to be sky.

Sometimes the worst inheritance is the one that teaches you the arithmetic of worth. Sometimes the sister who thinks she’s won walks away with a receipt and not the thing it proves. The lake taught me that secrets keep their own calendars and that justice prefers to arrive in work boots, not a cape.

Thanks for listening. If this found you, tell me where you are. Your voice—like every artifact we lift with both hands—matters.

That night, long after the lights at the dig clicked off and the frogs tuned the shoreline, I dreamed of the hospital chair where I learned how to sleep with one ear. The vinyl stuck to my skin and the clock on the wall talked in knocks. In the dream my mother was laughing, not the brittle laugh from the last months but the one that tripped on itself when Dad burned the garlic. I woke with my cheek damp and the old chair ache still in my bones, and for the first time in years the ache felt like proof that love had weight, not just cost.

In the mornings, paperwork arrived like polite storms. The lawyer explained quiet title in sentences I could put on my tongue without choking. We recorded an affidavit of possession for the parcel, then added an occupancy memorandum that named me as life tenant with Eleanor’s blessing. It read like truth made legal: the dirt is yours, the doors are ours, the mornings belong to whoever wakes up first and makes coffee.

Sarah brought a graduate student named Luis who could read soil the way my sister reads property comps. He taught me how to lift a sherd like I was picking up a sleeping bird. We set a tray on my kitchen table and matched curves until a rim reconstructed its old circle and a handle found the thumb that had made it eight centuries ago. When the afternoon wind came off the water, the tray chimed faintly, and Luis grinned like a boy who had found a magic trick and wanted everyone to see.

News crews multiplied. Some were kind. Some wanted a fight. A man shoved a microphone at my face and asked whether I felt guilty, sitting on money while my community struggled. I told him history doesn’t become less true because a camera prefers a different story. Later, I wrote a check to the food pantry anyway, because decency isn’t a rebuttal; it’s an obligation.

Patricia texted a link to an open house announcement—Maple Drive, Sunday, 2–4. The photos looked like they’d been taken by someone who loved daylight and mirrors. I stared longer than I needed to at the kitchen where we had sung Happy Birthday off‑key a thousand times. Then I put on a blue dress and went.

The agent wore a blazer the color of expensive confidence. “Welcome in!” she said, almost making the exclamation point blush. I walked through rooms that remembered me, the baseboard nick in the hall from the year we tried a real tree, the dent in the mudroom bench from Dad’s toolbox. Patricia stood by the island, all angles and polish, explaining quartz like she had mined it herself.

“Maggie,” she said, surprised into using my name right. “What are you doing here?”

“Touring,” I said. “I hear the schools are good.”

She led me to the breakfast nook, where the light still did that golden thing it did on October afternoons. “You can’t just show up and—”

“And what?” I asked. “Remember my home?”

The agent drifted away when she realized the air had weight now. Patricia’s voice softened the way velvet hides a bruise. “We could still—look, if the TV deal grows, we could—”

“There is no TV deal,” I said. “There’s a documentary that funds a field school. The only money you and I ever had to discuss has already moved.”

A young couple walked past, whisper‑smiling in the way people do when they imagine a future they might afford. Patricia watched them and I watched her watch them. For a moment I almost reached for her hand. Then I remembered the Sunday notary and put my hands in my pockets instead.

Outside, on the sidewalk under the maple that always went red first, she caught my sleeve. “Maggie, please. I don’t want to be the villain in your story.”

“You’re not,” I said, and meant it. “You’re the proof.”

We stood there with the leaf shadow moving over our shoes. “Proof of what?” she asked, almost childlike.

“That I don’t have to win against you to have a life,” I said. “I just have to live one.”

She let go of my sleeve. I walked to my car and didn’t look back, which is a kind of forgiveness no one teaches you but yourself.

A week later the District Attorney’s elder justice unit called me in, not because I had filed charges—I hadn’t—but because the bank compliance officer had flagged the old transfer during a training review. The ADA wore a tie that had made better choices than his hair. He asked if I wished to cooperate if needed. I told him I did not want my sister in court; I wanted her in a better story. He nodded like a man who had seen hundreds of worse families and wrote “declines prosecution” in tidy print. He asked if I understood that decline wasn’t immunity, and I said yes. Choice carries its own record.

The Tribal Historic Preservation Officer returned with elders and two teenagers who carried notebooks with the care of people who will fill them. We walked the perimeter together. We paused when they paused. We answered when they asked. Sarah reoriented two grids. We moved a spoil pile. Listening, I learned, is the fastest way to make time behave.

At dusk one of the elders stood at the edge of the dig and spoke words I didn’t know but felt anyway, the way you feel bass through a wall. We lowered our heads without being asked. Later he shook my hand and said in English, “Thank you for doing this like it matters.” I told him it did and that I was only learning how to prove it.

Eleanor’s world unfolded beside mine in the daily ways that matter more than declarations. She could coax flavor from onions the way Sarah coaxed shapes from soil. She taught me to salt earlier and apologize later. I taught her Dad’s old trick for unsticking a window by talking to it first. On Sundays she did crosswords with a pencil she would not give up. I read the journal again and again until the pages smelled like me too. We argued once about the right number of minutes to steep tea. We were both right and both wrong and laughed into the steam.

The easement negotiations turned out to be less knife fight and more committee meeting with snacks. Our lawyer pushed for stepped payments tied to milestones; the museum agreed with relief. The Nations signed as co‑stewards. We created a community advisory board that met under the carport with folding chairs and lemonade and the kind of minutes that make people feel seen. When the first check arrived, I cried again, because it was not the number; it was the line item that said the future is something you can budget for.

One afternoon, Jennifer from National Geographic sent a rough cut. In it, my hands looked competent and older than I felt. My voice sounded like my mother when I said the word careful. Patricia did not appear, not because they had cut her, but because she hadn’t been around. Stories don’t exclude people; people exit them.

On a blue‑cold morning in November, the crew found a cluster of beads that glowed like deep water. Luis lined them on black felt and whistled low. “Necklace, likely,” Sarah said. “Or a repair. Someone sat where you’re standing and threaded this while the stew simmered.” I tried to see that person’s hands. They were brown. They were clever. They were tired from a good day.

The foundation’s first awards day filled my porch with voices. The girl who would receive the inaugural scholarship wore a jean jacket stitched with flowers and a grin stitched with bravery. She shook my hand like a colleague. “I want to be a lawyer,” she said. “But the kind that keeps people out of court.” I told her the world keeps making new kinds if you insist.

That night, I wrote another letter I will never send to Dad. I told him the maple at Maple Drive still goes first. I told him Patricia is learning to live inside her own decisions without using mine for insulation. I told him the dock board on the right still squeaks and that Eleanor has a laugh that lives in the rafters after she leaves a room. I told him that forgiveness is not a transaction; it is a daily chore, like sweeping sand off the porch so the door closes right.

Winter put its teeth in the lake. The tents came down and the grids slept under tarps. Sarah said snow protects a site like a quilt. We pivoted to indoor cataloging. The kitchen table became a museum of tiny logic. Eleanor made stew that tasted like the color brown in the best way. I learned the difference between quiet and peace and stopped mistaking the first for the second.

Patricia sent a card at Christmas. It didn’t apologize or ask. It said, in handwriting that had finally outrun breathlessness, I hope you are well. The house sold. I moved into a smaller place near the office. It feels like something that fits. I put the card on the fridge with a magnet shaped like an orange and found that I was, in fact, well.

On New Year’s morning, I stood on the dock with coffee and the resolution to make fewer resolutions. The lake held a skin of ice that would shatter at noon. Smoke from someone’s fireplace stitched the trees together. I said out loud thank you to a place that had survived everyone’s plans for it, including mine. The words made a small cloud that the cold ate kindly.

In the spring, when the crew returned and the frogs started over and the maple made green coins, we opened a new square closer to the waterline. Within a week, a post pattern emerged—an outline like a house drawn by a child who knows where stories begin. “Domestic structure,” Sarah said, reverent. “Which means we get to imagine not just how they lived, but how they loved.”

At the edge of the square, a small object waited in the soil like a decision. Luis brushed until a shape made itself true. A tiny carved animal, worn by thumbs, the kind of thing you carry in a pocket or give to a child when the storm is loud. When he placed it in my palm, it was warm from the earth and warmer from whatever hands had held it before mine.

I stood there with a toy from eight hundred years ago and understood like a bell what the lake had been trying to tell me all year: inheritance is not a house or a check or an artifact. It is a line of hands handing forward care.

That night I left the porch light on until late, the way Dad used to when someone he loved was still on the road. Eleanor laughed at me and then left it on too. The beam threw a long shape across the path to the dig, and for a moment it looked like a road that had always been there, waiting for us to notice.

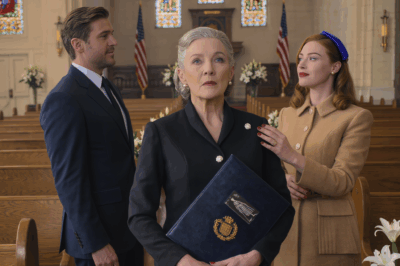

The winter after the first season, I finally let myself remember the funeral properly, not as a list of logistics but as a day with weather and sound. The church smelled like lilies and lemon cleaner. Patricia arrived late, beautiful and brittle, and kissed the air beside my cheek. People said my father was a good man, and I wanted to stand and say he was, but also he was a tired one and a complicated one and that goodness is not a fence you stand behind, it is something you carry until your hands shake. I folded the words and put them in my pocket like a tissue. After the service, Eleanor stood a careful two pews behind me, grief contained like water in a good bowl. When it was over, she touched my sleeve and said, “He asked me not to make anything harder.” I told her I didn’t know how to make anything easier and she said that was all right; time is stubborn but persuadable.

In February, the easement papers were ready. The county courthouse had the specific tired of buildings that have heard every kind of promise. The clerk’s window rattled when someone closed a door at the other end of the hall. Our lawyer slid the folder toward me and tapped the signature flags with a pen that clicked like a metronome. I signed my name until it stopped being a name and became a shape that meant: I choose this. Eleanor signed the occupancy memorandum with a small flourish, then squeezed my hand under the table like a secret passed in class. Outside on the steps, Sarah hugged us both and said, “Stewardship looks good on you.”

A week later, a thin letter arrived from Patricia. No stationary, just the kind of lined paper that makes you sit up straighter. She wrote that Maple Drive had closed, that she’d paid the capital gains like a person who had learned the price of keeping what doesn’t fit, and that she had moved into a small rental with south light and a stubborn radiator. She did not write I’m sorry. She did write, I am trying to be the kind of person you could call. I put the letter in the same box as Dad’s journal, not because they were the same, but because they belonged to the same story.

When the thaw came, the site opened with a community day. We set out card tables with coffee and a tray of cookies from a bakery that still uses butter like it believes in it. Elders spoke first. The teenagers who had been watching us all winter asked hard questions about custody and display and who gets to tell what. We answered with contracts and then with something better—chairs and agendas and the admission that we would need to keep answering for a long time. A little boy in a dinosaur hat stared at the sifter like it might produce a T‑Rex if he wished hard enough. He found a flake the size of his thumbnail and looked at his mother like he had pulled a star through a screen. She high‑fived him, then me, and the three of us stood there smiling the way you smile when a day remembers to be good.

The rough cut became a final cut. The episode aired on a Thursday night and the phone blinked for hours like a polite firefly. Messages came from people I hadn’t heard from since high school and people I had never met who wanted to tell me about their grandmother’s cedar chest and the coins their uncle found plowing. I answered as many as I could with a template that said thank you and please contact your local historical society and also remember: taking care of the living is a kind of preservation too.

Eleanor and I settled into a rhythm that felt like a porch swing: back and forth with room for weather. We burned one batch of cornbread but ate it anyway with enough butter to forgive it. We learned the way each other’s patience frayed at different edges and how to hem it up before it tore. On nights when the lake had opinions, we read to each other from the journal and made guesses about the kind of day the person who lost the bead had been having. Maybe a baby wouldn’t sleep. Maybe a sibling had moved to a village two days’ walk away. Maybe nothing happened except dinner and stories and the small miracle of hours you don’t have to fix.

I went to see the ADA one more time, not to change my answer but to give it roots. I told him the compliance letter had frightened me less than it would have a year ago, because I understood the difference between consequences and revenge. I said if they needed my statements I would give them, but I would not ask for anything more than what we had already made right. He nodded and said, “Most people come in asking for a hammer.” I said I had been carrying hammers my whole life. It was time I learned to build with something else.

On a Tuesday smelling faintly of rain, Patricia asked to visit the lake. She texted first, and she brought nothing except a bag of oranges and a look on her face like someone who has practiced not making noise. We walked the path to the water without filling it with talk. At the dock she stood with her hands in her coat and said, “I thought money would make me safe.” I said, “Me too.” She asked if she could help at the site. I told her yes, but that helping would mean listening, and that listening sometimes means hearing your name in a story you don’t like. She said she could try. Trying is a verb I can work with.

By late spring, the outline of the domestic structure near the water was clear enough that even my untrained eye could see the rooms. Sarah showed me where a doorway might have been and how the packing of the postholes told a story about weight and weather. “It stood for a long time,” she said, palm on the soil like a doctor’s hand on a ribcage. “It failed slowly and with grace.” I wrote that down, then realized she had given me a sentence about the house and, accidentally, a sentence about my family.

The day we cataloged the carved animal, the porch filled with neighbors who brought what they had: quilts, a jar of nails that someone’s grandfather had saved in a coffee tin, a song. One of the elders picked up the little figure and told us a story in his language, then translated only the last line: “We keep each other.” He set the animal on the felt and patted it once, the way you pat a dog that knows the way home.

On the first truly hot afternoon, Eleanor dragged an old fan from the hall closet and we listened to it tick like a metronome for summer. She fell asleep with a book on her chest and her reading glasses slid down her nose. I sat beside her and watched her breathe and tried on the word contentment like a dress you’re not sure you can afford. It fit.

I still go to the cemetery. It is not a pilgrimage; it is a small visit to a place where names sit quietly and let you say the things you should have said sooner. I tell Dad about the bead and the carved animal and the teenager who decided to apply to the state university because a grid square taught her she could hold history in her hands. I tell him about Patricia peeling an orange on the dock and handing me the first piece without making a speech. I tell him that I forgave him by accident one afternoon while labeling bags, the forgiveness arriving like weather does—noticed only after it has changed the light.

Summer brought dragonflies that wrote bright cursive over the water. The crew worked early and late and took the middle out of the day like a sandwich. We covered the squares at noon and uncovered them again at four. In the evenings the lake wore a gold shirt and every problem looked, if not smaller, then at least surrounded by beauty. One night a storm charged up from the far shore and the excavation lights went off all at once, the site going from stage to hush in a blink. We stood on the porch counting seconds between lightning and thunder, and when the rain finally came, it came as if someone had been saving it up. We pulled the tarps tighter and trusted what we had built to hold.

That trust, I’ve learned, is the real inheritance. Not the land, not the easement, not the checks that arrive in neat envelopes. It is the daily choice to keep each other, to listen, to write minutes and wash cups and tell the truth even when it doesn’t flatter anyone. It is the kind of wealth that makes you reach for another chair instead of another lock.

If you have read this far, you already know what the lake taught me in a language I can finally speak: some secrets are seeds. You plant them with care, and they become rooms to live in. And some debts are not to be collected but to be composted, and out of them comes a garden that feeds more than you imagined.

We left the porch light on again that night, for no reason except that someone might be on the road, and because both of us like the way it throws a long, kind shape down the path. Somewhere out beyond the dark, a chorus of frogs auditioned for a role they already had. The fan ticked. The house breathed. The lake kept its counsel. And I felt, at last, entirely at home.

Patricia’s point of view arrived on a humid Sunday like a mirror held at a new angle. She woke in the apartment that faced south and made strong coffee in a mug that said Busy, which was either a joke or a relic. She put on the blazer that used to feel like armor and now felt like a uniform—clean lines, clean ledger. Outside, the city hadn’t decided whether to rain. She drove to the open house she’d scheduled herself because delegating had started to feel like a way to hide.

She unlocked the door to a property she could have named with her eyes closed: the Maple Drive listing, but not the old one—this was a near twin three blocks over, her first solo after closing her own house. She set out booties and brochures and a bowl of wrapped candy, then smoothed her hair in the reflection of the black oven door and told her face to behave.

People came. Couples with elbows touching. A woman alone who measured windows with her gaze. A father with a toddler who discovered echo. Patricia said the sentences she had said for a decade and adjusted them in the places where truth had moved. She did not say schools as a sales bullet; she said it like a wish. She did not call the quartz countertops chef’s grade; she ran her palm over them and remembered Maggie’s hand on a hospital tray, steadying a cup for their father because the cup would not steady itself.

Halfway through the window, Maggie walked in wearing a blue dress that treated the room like a room, not a stage. Patricia felt her cheeks try to do something performative and let them rest instead. “You’re early,” she said, not unkindly. “Or right on time.”

“I wanted to see what you see,” Maggie said. She stood in the breakfast nook and let the light show its trick. “You were always right about this corner.”

Patricia watched the young couple with whispers move past and tried to name the sensation that wasn’t envy and wasn’t grief. It was a third thing: the relief of an accurate assessment. “It’s a good house,” she said, and what she meant was: I was not good in ours.

They stood together while the agent in her said words, and the sister in her listened for other ones. “If you need an inspector rec,” Patricia said at last, “I know a fair one.”

Maggie’s mouth did the little tilt that meant yes. She turned toward the hall. Patricia reached without thinking and caught the sleeve, then let go because the lesson had stuck. “I don’t want to be the villain in your story,” she said in a voice tuned to honest.

“You don’t have to be,” Maggie said. “You can be the part where the story gets better.”

When the last visitor left and the house exhaled its afternoon, Patricia walked the baseboards like a docent of small damages. She found the nick where a previous family had misjudged a bookshelf. She touched the dent in the mudroom bench that might one day hold a toolbox. She stood in the kitchen where light dome‑ed under the fixture and took off her blazer. She did not cry. Not out loud. But the room knew, and did not punish her for becoming a person who could hold two truths in one ribcage: I wanted and I took. I am learning to give back.

Weeks later, when the sale closed, she bought a simple plant with leaves that had to be dusted and set it by the south window of the apartment. She watered it on Thursdays and, sometimes, on days when she needed to do one thing right.

The museum opening day felt like a harvest and a first day of school. The building had the polished hush of public gratitude—stone that knew how to hold footsteps, banners that had been ironed into obedience. The exhibit title sat in letters tall enough to remind you to lower your voice. Beneath it, a smaller plaque acknowledged the Nations as co‑stewards, the State Archaeological Commission as partner, and, in a line that made my breath hitch, Clearwater Futures Foundation for community support.

We arrived early because Sarah wanted to walk the rooms alone first. She moved through the cases with a curator’s hands behind her back, checking mounts and labels the way a parent checks a sleeping child’s breathing. The carved animal sat on its felt like it had always belonged there and somehow also like it could jump down and run. The bead necklace we’d puzzled together lay in a crescent that refused to shine too loudly. A looped video played footage of the dig: the grid, the brush, the sift, the pause.

The elders came. The teenagers came with them, shoulders squared in shirts that tried to be serious. The THPO nodded at the language on the wall and then asked for one correction, which the museum staff made before the doors opened because that’s what respect looks like when it’s awake.

People flowed in: neighbors, donors, kids with field‑trip eyes. Jennifer from National Geographic tucked herself into a corner with a small camera and a smaller footprint. A docent explained provenience with a basket of oranges and a label that said please take one after you read. Someone laughed softly when they realized the joke carried a lesson.

I stood near a case and read the words I had helped write and felt the strangest sensation—pride without possession. The land was still mine by law, the easement still a ledger line, but the story belonged to more people than I could count, most of whom had been waiting longer than my language could track.

Patricia slipped in late, quiet as weather. She wore no blazer. She gravitated, as I had known she would, to the domestic cases—the hearth reconstruction, the pottery with soot lines like timelines. She stood for a long time at the doorway outline rendered on the floor and then at the bead crescent. When she reached for my hand, she did not perform it. She just reached, and I let our fingers know each other again.

An elder told the story of the carved animal, ending with the line he had translated for us on the porch: “We keep each other.” The words found the ceiling and stayed there, not as a slogan but as an instruction. The teenagers nodded like they’d just been handed an address and a key.

After the speeches, a little boy in a dinosaur shirt pressed his face to the glass and asked if the toy could play with him. His mother crouched until they were eye to eye and said, “It’s playing with all of us right now.” He accepted this without argument and asked if there would be cookies. There were.

Sarah clinked a plastic cup with a plastic spoon because no one had thought to bring a bell. “To the site,” she said, “to the people whose lives we can see a little better now, and to the living who showed up with care.” She looked at me, then at Patricia, then at the elders, then at the crew. “To doing it right, even when right takes longer.”

Later, after the crowd thinned and the museum stopped feeling like a festival and remembered it was a quiet place, Patricia and I stood under the title again. She took a breath the way divers do before a new depth. “I’m trying,” she said. “Not for a performance. For a life.”

“I can tell,” I said. “Trying is how lives happen.”

We walked out into evening. The banners stirred. The air had that after‑rain electricity that makes skin remember it has pores. Eleanor linked her arm through mine and steered us toward the car like a small boat heading home. Behind us, through the glass, the carved animal kept its counsel. In front of us, the road made the same long, kind shape it always makes when the porch light is on.

News

BREAKING: My Son Gave Me a Choice: Either Serve His Wife or Leave. I Smiled, Grabbed My Bag…

My shopping list was still in my pocket when I walked through the apartment door, arms full of groceries from…

I Thought I Knew My Children Until The Plumber Discovered What They Were Hiding In The Basement and Said: ‘Pack your things and leave the house immediately!’

My name is Anita Vaughn. I am sixty‑three years old, a widow, and for more than four decades this house…

I Counted 21 Times My Children Interrupted Me While I Read My Husband’s Will. They Smirked, Whispered, And Looked At Each Other Like I Didn’t Exist. Days Later, I Pressed Record As The Lawyer Entered.

The first thing they did was toss my husband’s muddy work boots into the trash—the ones he’d left by the…

I Won The Biggest Lottery Jackpot In State History — $384 Million — But I Didn’t Tell Anyone. I Called My Mom, My Brother, And My Younger Sister, Saying That I Was Short On Money And Needed Help.

My name is Mark. I’m thirty-two, the oldest of three, and the family’s invisible cushion—always catching, never caught. I’m a…

BREAKING: When I Learned My Parents Gave The Family Business To My Sister, I Stopped Working 80-Hour Weeks For

The pen hovered over the document, my father’s signet ring glinting under the office lights. I watched, frozen, as he…

JUST IN: At my husband’s funeral, my daughter-in-law mocked my dress. She had no idea who I was.

The chapel was silent except for the low hum of the organ and the soft scrape of shoes against marble….

End of content

No more pages to load